The Pursuit of Happiness

The prospect of writing My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet's Life in the Palestinian Century filled me with a fairly cavernous sense of dread.

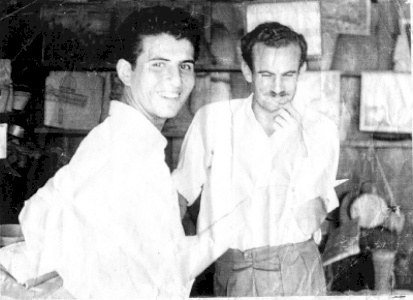

The book in question is a life and times

of Taha Muhammad Ali, a marvelous Palestinian poet who was born and

grew up in Saffuriyya, a Galilean village that Israel bombed during

the 1948 war and demolished in its wake. After a difficult year

spent in Lebanon as refugees, Taha and his family snuck back across

the border and into a place that had been Palestine and was now

officially, if not emotionally, Israel. Like the other Palestinian

citizens of the new Jewish state, they were subject to the harsh

restrictions imposed on them by the military government, which

controlled much of their lives until 1966. An autodidact (he had

just four years of perfunctory village schooling), Taha has spent

nearly sixty years operating a souvenir shop near the Church of the

Annunciation in Nazareth. At the same time, he has taught himself

much of classical and contemporary Arabic literature, absorbed

copious quantities of English and American poetry and prose, and

evolved, slowly but with a stubbornly single-minded kind of

determination, into a writer of formidable power. Most of his poems

well up from the hard ground of his Saffuriyya childhood, at once

mourning the loss of the village and celebrating it as a living,

breathing, crowded place. In a sense, Taha has managed to preserve

by way of his expansive imagination what has been obliterated in

physical fact.

I, for my part, am an American-born Jew

who has lived in Jerusalem for much of her adult life – assuming a

sort of bifocal national identity in the process. I carry two

passports, American and Israeli, and I first came to know Taha when

my husband, the poet Peter Cole, began, together with Yahya Hijazi

and Gabriel Levin, to translate his work into English. Within

months of the outbreak of the second Intifada in 2000, Ibis

Editions, the small, non-profit press that Peter, Gabriel, and I

run together in Jerusalem, published a book of these translations.

We must have known in some inchoate way then that bringing out such

a volume – of Arabic poems inspired by a bulldozed Palestinian

village, translated by a trio of two Jews and a Muslim, all three

of them like the author himself, technically Israeli citizens –

was, in its small way, an act of protest. (“Us [the Jews] here and

them [the Arabs] there” had by then become the separatist slogan of

many liberal Jewish Israelis.) But it was only later, as the

situation around us worsened considerably and we grew to know Taha

much better, that I began to grasp the political, personal, and

artistic implications of this alliance, this

friendship.

Intrigued as I was by Taha’s person and

his poetry, the thought of writing a book about him was, as I say,

daunting. The idea of setting out across the narrative minefield of

Palestinian-Israeli history seemed at best masochistic, since –

before I’d put a single word on paper – I could already hear a

whole chorus of readerly complaints: I’d be damned by some

indignant partisan no matter what I wrote.

Yet the closer Peter and I became to

Taha and, ironically enough, the darker the political skies over

all our heads grew – one survey from around this time showed that

forty one percent of Israeli Jews supported the separation of Arabs

and Jews in places of entertainment, forty six percent were

unwilling to have an Arab visit their home, and sixty eight percent

objected to an Arab living in their apartment building – the more

such hesitations fell away and the more I came to appreciate Taha’s

undogmatic and ebulliently independent example. (Those numbers

would, I’m certain, be still more disturbing today, as the

ominously strong showing of now-Foreign Minister Avigdor

Lieberman’s xenophobic party, Yisrael Beitenu, in the most recent

Israeli elections shows.) “Taking sides” is not the point here,

because I do not consider myself and Taha – or Jews and Arabs,

Israelis and Palestinians, for that matter – to be, at heart, on

different “sides” at all; as I see it, and as the book tries to

make clear, more joins than separates us, and the failure to focus

on that shared realm of experience has had, and continues to have,

a catastrophic effect on both peoples.

The notion of “taking sides,” though, is

so central to the way the Middle East is thought, written, and

yelled about that serious work is required to cut through it. One

commentator is dubbed “pro-Palestinian,” another “anti.” Professor

X gets blackballed as an “Israel hater,” while columnist Y is

smeared as an “Islamophobe.” There are, amazingly, people who

choose to spend good hours every day scouring newspapers,

monitoring radio programs, dowsing the internet for any sign of

perceived bias, keeping in hand at all times what amounts to an Us

vs. Them scorecard – just waiting, that is, to take offense and to

pounce. Such thinking is based on the highly dubious (but rarely

questioned) zero-sum premise that what is good for the Arabs is bad

for the Jews, and vice versa.

Alas, despite its best intentions, the

media also falls prey to the trap that “balance” has become, as if

every Arab who opens her mouth before a TV camera must be followed

immediately by a Jew – preferably of the same height, weight, and

hair color – who will counter her opinions word for word and in

precisely the same allotted number of milliseconds. I am

exaggerating, of course – but only slightly. Granted, most

journalists are simply trying to be responsible, professional, and

fair. But there are other forces at work here, and all too often it

seems that fear is stoking this obsession with balance. (Who knows

when those watchdog packs might attack?) For an American reporter

to have his or her “objectivity” seriously questioned is tantamount

to a charge of professional treason – or so the thinking goes. The

inadvertent effect of such wholesale equalizing is, however, a

different sort of skewing. Every actor in this terrible drama is

reduced to playing either a representative Palestinian or a

representative Israeli, and to reciting his well-rehearsed lines

right on cue.

Meanwhile, lost in all this is what

Henry James called “the spreading field, the human scene” – that

is, the dynamic interplay of a whole host of very specific

individuals, each with his or her own complex temperament and

tastes, fears and longings. Lest we forget, this lies at the core

of the conflict, and it is also the very essence of what drove me

to want to write about Taha Muhammad Ali in the first place: a deep

desire to understand how, despite everything that Taha has endured,

he has managed to remain so alert and joyful. If Taha has been

angry – and his poetry acknowledges that, at times, he has – he has

not let this anger flare into hatred but has turned it into an art

and a generosity of feeling that seem almost to defy history. And

maybe geography as well, since his poetry reaches far beyond

national borders to speak both to those who know the land

intimately and to those on the opposite ends of the earth. It is

profoundly local – and utterly universal.

But the book is not just about Taha

Muhammad Ali. In setting to work on what turns out to be the first

full-fledged biography of a Palestinian writer to be published in

any language, I quickly discovered how this one life ripples

outward and eddies into the lives of many others as well. And as I

wrote, I wanted to account for the whole panoply of thought,

feeling, and experience that I encountered when I came to know Taha

and all that surrounds him. In order to do so, I steeped myself in

his rich (and, to the West, little-known) culture – absorbing the

Arabic language, Palestinian literature, history, food, folklore,

politics, music, and so on and on. At the same time, I came to know

what felt like a galaxy of remarkable people whose lives have

somehow intersected with his own: Arabs and Jews, peasants and

poets, soldiers and shopkeepers, Saffuriyyans and Tel Avivans,

Baghdadis and Philadelphians. It is this intersection of lived

lives and, at their core, endangered dignities that this book is

really about and that drew me past my dread.