How do we say Nakba in Hebrew? Reflections on teaching Jews in Israel about the Nakba

How should the topic of the Palestinian right of return be dealt with by the Israeli educational system? How should it be approached when the reality in Israel is that the topic is one “we don’t talk about”? How can we start a conversation, get people to listen, overcome objections?

The usual Israeli responses

to the idea of the right of return are almost always bound up with

inflammatory statements which heighten fears of Jewish-Israelis

that they will once again become victims. They combine apprehension

about potential future victimization with refusal to accept

responsibility for Israel’s unjust treatment of the Palestinians,

in the past as well as today. The result is that no serious,

nuanced discussion of the Nakba and the Palestinian right of return

takes place in Israel today. Jews in Israel who wish to be part of

the solution to the conflict and live in an egalitarian society

must be part of that discussion. Raising the issue in the

educational system is essential to encouraging public

discussion.

Zochrot, whose goal is to increase Israeli awareness of the Nakba

and the right of return, has prepared educational materials aimed

at Jewish-Israelis focusing on these two issues. We recently

published a Learning Packet entitled How do we say Nakba in Hebrew? for use in the Israeli education system - those who are

part of the formal educational system as well as others. This

unique Learning Packet contains the first set of lesson plans and

educational resources in Hebrew for teaching about the

Nakba.

"That’s Not

Something We Talk About: The Palestinian refugees’ right of

return"

Unit 12 from the Learning Packet: "How to say Nakba in

Hebrew?" (available on Zochrot's website)

The lesson aims are

to elicit questions about the meaning of return for Palestinians

and Israelis. The lesson opens by providing information about the

Palestinian refugees, how and at whose hands they became refugees

and what their situation is today. It continues by discussing

Israel’s decision to refuse to permit refugees to return during the

war and how it prevented them from doing so, as well as

international recognition of the right of return as expressed in UN

Resolution 194. The second part of the lesson considers the meaning

of return for Palestinians, using a photography exhibit by

Palestinian youth from the project “Dreams of Home” created by

Lajee Center in Aida refugee camp, Bethlehem. It continues with

statements from Badil’s information packet by Palestinians about

the right of return. The lesson ends by opening a discussion

through the questions: What does the right of return mean to us as

Jews in Israel? What happens to us when we hear about the right of

return? How are we affected by the fact that many of us don’t

recognize the right of return and are not even willing to discuss

it?

The Learning Packet is aimed at schools

which are, for the most part, Jewish-Israeli, where Zionist

discourse reigns, and is intended primarily for educators in the

formal and informal school systems, including colleges,

universities and teacher training institutions.

The Learning Packet is appropriate for

students aged fifteen and older, and contains lessons, activities

and resources for learning about the Nakba from various

perspectives, addresses a range of topics, and employs a variety of

educational methods. It includes units based on literary texts,

artwork, historical material, film, and a variety of other media,

and allows teachers and students to approach the topic modularly,

from their own political, emotional and social perspectives. Each

lesson unit in the Learning Packet can stand alone; used in

combination, they encourage different learning processes. For

example, the Learning Packet opens by referring to the student's

personal situation, moving to what they know about where they live,

about themselves, their families, the society in which they live

and the history they are familiar with. It then moves on to more

general discussions of the Nakba. Another trail in the packet looks

first at the past, then at today’s reality, and concludes by

considering possible futures.

The Learning Packet draws on the

principles of critical pedagogy, and links them to

Zochrot’s political perspective. According to the tradition

established by Paulo Freire, critical pedagogy is learning that

involves commitment, relevance and a call to take action. It

assumes that learning depends on context, on one’s location and on

one’s society, so that learning about the Nakba must be different

for Jewish-Israelis and for Palestinians. The critical pedagogical

approach allows us to undertake a process of educational change,

without suddenly pulling the rug out from under the students. As

part of the critical process, students face their own resistance to

dismantling the core Zionist narrative, re-viewing their own ideas

and basic assumptions, and even changing them.

It is an educational procedure which

imparts knowledge and simultaneously involves a political-emotional

process of reworking the new information as well as the old. For

Jews in Israel, learning about the Nakba involves not only gaining

new knowledge, but also understanding, and sometimes discovering,

that much information about their own past has been deliberately

concealed from them. That knowledge structures the individual and

collective fundamental assumptions which are based on a

Zionist/nationalist perspective. Learning about the Nakba, then, is

not only about gaining knowledge, but is also a process which

raises fundamental questions about Israeli identity and the Jewish

state that must be faced and dealt with emotionally as well as

politically.

Tours and

Signposting

Zochrot organizes tours to the sites

of Palestinian villages that were destroyed in 1948, the existence

of which is unknown to many people in Israel. The tours invite the

public to re-encounter the landscape with new eyes, retracing the

paths of the destroyed village and hearing its stories as told by

refugees and scholars. During the tours we also post signs in

Hebrew and Arabic marking village sites and distribute booklets

containing original research on the village, testimonies,

photographs, and maps. Zochrot Booklets (in Arabic and Hebrew) are

all available on Zochrot's website. Unit seven of the learning

packet offers different pedagogical methods for processing the

tours with students.

In preparing the Learning Packet, the

following question arose: How can we create an educational process

which empathizes with the students but also avoids pandering to

their deeply-held Zionist assumptions? Empathy is both the basis

for the educational process and what makes it possible. Empathy,

understanding, and sensitivity to the situation of Jewish-Israeli

students are all part of the educational process, along with

challenging and objecting to Zionism’s basic assumptions – asking

questions, providing information, recounting unfamiliar stories,

deconstructing the unspoken assumptions of racism, power relations,

colonialism, Europeanization, and so on. Students who were taught

using the Learning Packet report that, in addition to what they

learned about the Nakba and about Palestinian refugees today, many

questions arose and challenged their view of the world: What is

history and what is truth? Who writes the history? Why do we tend

to pay attention to and believe written, rather than oral, history?

How does the concept of “narrative” serve the stronger side, the

one with power? What obligations does learning about the Nakba

impose on us?

Noa Sandbank-Rahat, a member of a group

of Israeli educators who learned about the Nakba under the auspices

of Zochrot, and was part of developing the Learning Packet, had

this to say about the process she herself went through in learning

about the Nakba:

I came to Zochrot with great difficulty, even anxiety, at the prospect of going back past 1967, of reaching “Year zero” – 1948 – saying the word “Nakba” in Hebrew. I actually felt threatened, helpless, guilt-ridden.I first came into contact with the Nakba with a group of other educators. Studying with that group allowed me to begin a journey that started with the eyes. Looking, first of all, at the process of forgetting, at memory’s shadow. Gazing at that shadow allowed me to recognize the existence of the memory itself. And then, very slowly, like an archaeologist caressing with his brush each discovery that emerges from the sand, I was able to begin touching that place, touching the Nakba.To my great surprise, the process of looking freed me of those fears, that helplessness. Learning about the Nakba as part of a group allowed me to be in two places at once – the one where I mourned what had occurred, mourned the Nakba that surrounds us, what it did to me and to us all; and the other in which I seek ways to redress, to change and to fix in order to create a different present and a different future. Instead of being paralyzed by guilt, my sense of responsibility now motivates me to act.

So – how do we develop an educational

program on the Nakba for Israeli Jews?

This is the question which guides the

unit in the Packet dealing with the right of return, the one

entitled "That’s Not Something We Talk About: The Palestinian

refugees’ right of return." The lesson combines two main questions:

what is the right of return for Palestinians? What does it means to

us as Jews in Israel?

The Map

Activity

In this activity,

participants recreate a large-scale map of all the Palestinian

localities destroyed in the Nakba. The map is actually a grid, made

of adhesive tape or rope that correlates to the actual longitude

and latitude lines of the map of Israel/Palestine.

During the activity,

participants are “returning” individual cards representing each

village to their correct location on the map according to the

longitude and latitude number printed on the card. The participants

can also personalize their cards or decorate the map using chalk,

colored stones, stickers, ribbons… At an open microphone,

participants can voice their personal connection to the village or

to the community located at its site today. Instructions for

building the map can be found at: http://www.zochrot.org/index.php?id=556

In workshops with educators where the

Learning Packet was presented, the discussion also centered around

the questions: What happens to us when we hear about the right of

return? How are we affected by the fact that many of us don’t

recognize the right of return and are not even willing to discuss

it? It raised the sort of fears and apprehensions I referred to

earlier, and provided a place for expressing them. But what also

came through was a feeling of helplessness in the face of such a

complex and fundamental issue – that the chance of any solution was

fainter and less likely than ever. Such helplessness is accompanied

by a fear of raising the issue in front of students, of being

labeled a leftist, an “Arab lover,” as well as a pedagogical

concern about leaving Israeli students with feelings of guilt and

injustice. But these are exactly the issues that must be confronted

in order to arrive at a solution and bring about reconciliation.

Feelings of guilt need not be paralyzing; they can lead to

accepting responsibility and action for change.

The question, “What does the right of

return mean to us as Jewish Israelis?” makes it possible to conduct

a discussion aimed at constructing a different reality. A reality

of cooperation, one in which Israeli Jews are aware of and accept

responsibility for Palestinian suffering as well, but also be part

of developing mechanisms for justice and reconciliation. Talking

about the right of return allows us to see possible solutions to

the conflict rather than letting it continue. We borrowed from the

methodology of the South African Truth and Reconciliation

Commissions as an example of Transitional Justice as a mechanism

for solving a conflict elsewhere, one not our own. Learning about

other conflicts in the world gives us the opportunity to see that

many ways exist to deal with and solve violent conflicts. The

solutions aren’t perfect, but learning about them can make us think

about and plan solutions and political structures which don’t

sanctify the Jews as the sole nation possessing rights here.

Wisconsin

Lawyers by city

Landscapes of Home

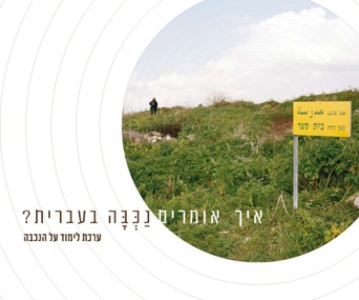

What do we see when we look at the

landscape? What don’t we see?

Unit 2 from the

Learning Packet: "How to say Nakba in Hebrew?" (available on

Zochrot's website)

This lesson aims to give Jews in Israel

a starting point to learn about the Nakba.

In this lesson, we look at images of

various places in Israel, that are well knows for Israelis, where

remains of Palestinian localities destroyed since 1948 are found.

We use the photographs to look at familiar surroundings with fresh

eyes to recognize traces of the Nakba in the landscape and learn

how Israel worked to erase evidence of the Nakba and Palestinian

heritage.

Recognizing in the Israeli surroundings

the remnants of Palestinian life exposes the practices employed to

erase the Palestinian Nakba from the Israeli landscape. These

practices of erasure appear again and again in various sites

throughout the country. We’ve found that these practices of erasure

can be identified and grouped into different “series.” Examining

one example of each series can teach the participants about the

series as a whole, about the particular practice of erasure. By

practicing the pedagogical methods “reading photographs” we can

develop a new way of examining our surroundings, one which also

includes seeing the Nakba.

Teaching Jews in Israel about the Nakba

educates us for the future. It challenges the core Zionist

narrative, and aims to create and encourage thinking about civic

perspectives. It reexamines the fundamental assumptions of

Zionist/nationalist education. For Israeli Jews, learning the story

of the Nakba challenges the basis of their collective identity,

fracturing it again and again. Jews in Israel are also obligated to

search, research, and examine our own history. Such learning has

the potential for us to play an active role in the struggle to

create a future of reconciliation and establish relations between

Jews and Palestinians based on accepting responsibility,

recognition and respect. Learning about the Nakba involves not only

learning about the injustice and plunder Palestinians suffered at

Israeli hands, but also learning about aspects of the history of

Jews in Israel which have been silenced.