Documenting Palestinian Refugee Claims: The Unfinished Job

Palestinian refugees may be one of the longest-standing refugee cases in the world today; they are also one of the most documented group of refugees. Recent years have seen the digitization of housing and property records held by the United Nations. But there remains a gap in documentation – registration of those records still held by refugees themselves.

There are literally hundreds of thousands of documents providing evidence of Palestinian housing, land and property claims dating back to the period before the unilateral establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and the mass displacement of 80 per cent of the Arab population living in that part of former Palestine that became the new “Jewish state”.

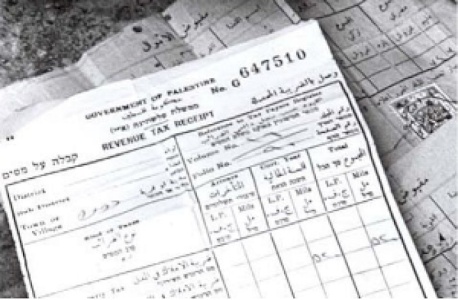

These include Ottoman land records, British land registration files and tax records, aerial photographs of Palestine from the first and second world wars, the archives of the Refugee Office of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, documents in the family files of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), and the Israel Lands Administration records charting the transfer and subsequent use of Palestinian refugee lands.

In the 1990s the UN undertook to digitize the UNCCP land records. This included 5,625 maps, approximately 210,000 double-sided owners index cards, and 1,641 35mm films of British Mandate land registers.(1) A similar process to digitize UNRWA records is also underway. It is estimated that UNRWA family filescontain more than 16 million documents, including land deeds, utility and tax bills, among a host of other documents. (See, Ron Wilkinson, “Preserving the Palestine Heritage,” Majdal 26, June 2005)

While these long-overdue efforts to preserve the heritage of Palestinian refugees are commendable, there remains at least one significant gap. Almost everyone familiar with the Palestinian refugee question has seen the image of the Palestinian refugee and his/her key. Sit down with refugees in any camp in the region, or further abroad, and many will soon pull out old documents attesting to their life in Palestine before they became refugees.

Many of these documents are in poor condition, some having survived successive waves of displacement, others plucked from safety before Israeli bulldozers push down the walls of yet another house in the occupied territories. Unlike records held by the UN, however, there is no comprehensive database of the hundreds of thousands of documents still in the hands of refugees themselves. And there is no current effort to preserve these documents.

Learning from Bhutanese refugees

Each refugee case is unique. There are, nevertheless, universal principles and best practice that can be transferred from one refugee case to the next. The response of Bhutanese refugees to their forced exiled in the 1990s is one example that may be instructive if not inspirational for Palestinians in dealing with the preservation of documents still held by refugees themselves.(2)

Today there are more than 100,000 Bhutanese refugees. The majority reside in seven camps in Nepal. These refugees, who comprise about about a sixth of Bhutan’s population, were expelled from their homes in the southern districts of the country in 1990-91. Like Palestinian refugees, the Bhutanese refugees want to return home. Earlier this summer, hundreds of Bhutanese refugees attempted to return home on their own but were not permitted to cross the border.

Bhutanese refugees are ethnically, culturally and religiously distinct from the ruling Bhutanese elite. The Bhutanese government has thus been unwilling to allow the refugees back. Refugee properties have been expropriated, resettled, in some cases towns have been given new names, while refugees were stripped of their citizenship. The central argument of the Bhutanese government has been that the refugees did not originate from Bhutan and are therefore not Bhutanese citizens.

In the late 1990s, AHURA Bhutan – a non-partisan and non-governmental human rights group – set up a project to document the history of the Bhutanese refugees. The primary objectives of the project are to prove that residents of the seven refugee camps are bona fide Bhutanese citizens with incontestable documentary evidence of their origin, nationality and property rights in Bhutan. The goal of the project is the early return of Bhutanese refugees and full restitution of their property and fundamental rights.

Actual work began at the beginning of 1999 with 18 full-time staff members. This included three in organization and management; three in computing; five in research; seven as general volunteers. Information was collected from volunteer camp residents and was subsequently verified by former village headmen, deputy headmen and village elders resident in the camps.(3) By March 2000, when the first stage of the project was complete, AHURA-Bhutan had collected documentary evidence from half of the entire Bhutanese refugee population.

Information collected in the camps was digitized and stored in a database for easy access. The database was produced in CD form to be used to lobby for the early return of the refugees. From a map of Bhutan one is able to click on a district, town and then see the list of families displaced from that area. Family and property details, plus important documents are organized and collated on a family, block and district basis. Documentary evidence includes Citizenship Identity Cards, Land Tax Receipts and photographs of houses and lands.

The project team, however, was unable to complete the documentation of 100 percent of the refugee population. According to AHURA-Bhutan, some of the refugees were either unwilling to participate or apathetic, doubting that the project would contribute to a solution to their plight. There was also evidence that some of the population were misinformed and misguided by various factions. Nevertheless, the project is an amazing example of how refugees themselves can contribute to building their case for return and restitution.

Towards the 60th anniversary of the Nakba

Palestinian refugees and IDPs do not need to wait for a peace agreement to work towards restitution of their homes, lands and properties. As one commentator has observed about refugees from Guatemala who organized themselves into commissions to negotiate directly the terms of their return and restitution, the refugees did not wait for peace, they helped to forge it and thereby became actors in the process of building peace and democratization.(4)

Following the example of Bhutanese refugees, Palestinian refugees could embark on a project to record their own claims for return and restitution. This could include digitization and registration of documents still held by refugees, including land titles, tax receipts, photographs, as well as oral history accounts of their expulsion and description of their homes and properties before the Nakba.

All of this information could be organized in digital format on an easy to use CD or DVD Rom. Users could click on a district of a map of Palestine, and then on a village to see the various refugee claimants, their story and their documentation. The project would have several benefits:

1) it would provide a means for refugees to preserve their

documents, which are more than fivedecades old. Each refugee would

retain their original document/s, but also receive a CD of the

digitized document/s, as well as a quality reproduction;

2) it would raise awareness about Palestinian refugees and their

claims;

3) it would provide a mechanism for refugees to learn about their

rights to housing and property restitution and a way to participate

in the process of findingasolution;and,

4) it would fill in the gap regarding documentation of housing and

property claims.

In two and half years Palestinians will commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Nakba. This might prove to be a useful date to work towards and to ensure that Palestinian refugees claims to homes, lands and properties will never be forgotten.

For more information about the Bhutanese refugees and the documentation project visit the website of AHURA-Bhutan, http://ahurabht.tripod.com.

Terry Rempel is a senior researcher at BADIL. He is also a Research Fellow at the School of Historical, Political and Sociological Studies at Exeter University.

Notes:

(1) Michael

Fischbach, Records of Dispossession, Palestinian Refugee Property

and the Arab-Israeli Conflict.New York: Columbia University Press,

2003, p. 338.

(2) This section is based on, Ratan Gazmere

and Dilip Bishwo, “Bhutanese refugees: rights to nationality,

return and property,” Forced Migration Review 7 (April 2000), pp.

20-22.

(3) Information about the documentation

project was disseminated to the refugees through leaflets, sample

demonstrations, and verbal information through volunteers. The

project team developed a standard collection format. Refugees came

to the project office in Damak and were interviewed by volunteers

trained in interviewing; anyother information which could not be

given by the interviewee then involved a camp visit.

(4) Galit Wolfensohn, “Refugees and

Collective Action: A Case Study of the Association of Dispersed

Guatemalan Refugees,” 19 Refuge 3 (2000), p. 14.