Palestinian Refugees from Syria in Lebanon: An Overview

The influx of Palestinian refugees into Lebanon started in July 2012, “after a string of mortar attacks upon the Yarmouk refugee camp killed 20 people”, and increased in December 2012, “when a Syrian jet bombed a mosque and a school inside the Yarmouk refugee Camp”.1

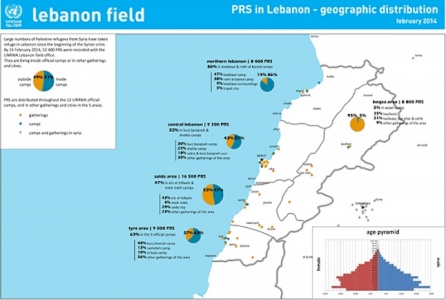

The history of Lebanese experience with Palestinian refugees underlies the current political response to the influx of Syrian refugees,[2] even more restrictive toward Palestinian refugees from Syria. This is manifest in the Lebanese government’s “reluctance to authorize the establishment of new refugee camps”,[3] leading to an overcrowding of already existing Palestinian refugee camps.[4] As a result, 51% of Palestinian refugees from Syria in Lebanon live in Palestinian refugee camps, in which space and resources are becoming scarce and triggering competition among refugees. With the increase of rental prices, many families share shelters. Only 6% of Palestinian refugees from Syria have a room for themselves, while 70% have to share it with three or more people.[5]

Perhaps the most challenging hardship affecting Palestinian refugees from Syria in Lebanon is entering the country. As early as 8 August 2013, Human Rights Watch reported that Palestinians fleeing Syria were being denied entry into Lebanon.[6] This event marked a change of policy that established new entry requirements for Palestinian refugees. A second change occurred in May 2014, when another report by Human Rights Watch drew attention to the issue.[7]

Until August 2013, in order to enter Lebanon Palestinians were required to present a prior authorization from Syrian authorities to leave that country, which had to be obtained at the Department for Immigration and Passports in Damascus upon presentation of their Palestinian Refugee Identity Card.[8] After August 2013, entry in Lebanon was granted to those Palestinians who presented one of the following:

a valid pre-approved visa which required an application made by a guarantor in Lebanon; a valid visa and ticket to a third country – meaning they were only transiting through Lebanon; a scheduled medical or embassy appointment; or if they were able to prove they had family already legally in Lebanon (a family member had to send a valid copy of their residency permit to the authorities as proof).[9]

On 8 May 2014, the Lebanese Minister of Interior announced new regulations affecting the entry of Palestinian refugees from Syria into the country. The new regulations require them to present at least an entry permit approved by the General Security,[10] a one-year or three-year residency visa, an exit and return permit, and/or a valid ticket to a third country, “in which case they can get a 24-hour transit permit”.[11] As a result, between 15 April and 31 May, the number of Palestinian refugees from Syria grew by only 73, a decrease compared to the previous six weeks.[12]

Although the Lebanese Minister affirmed that “[t]here is no decision preventing Palestinian refugees in Syria from entering Lebanon and passing through the country”,[13] a document leaked from Beirut’s Rafiq Hariri International Airport,[14] apparently from the security services,[15] instructed airlines not to transport Palestinian refugees from Syria to Lebanon:

No matter the reason and regardless of the documents or IDs that they hold, under penalty of fining the transporting company in case of non-compliance as well as return of the traveler to where they came from.[16]

On 3 May 2014, the date the document was issued,[17] the Lebanese General Security stopped 49 Syrians and Palestinians from Syria at the airport for using forged documents and deported dozens of Palestinian refugees back to Syria, even though they had told the authorities they feared being arrested for evading their mandatory army service.[18]

As a result of those restrictions, many enter and remain in the country illegally. Moreover, some Palestinian refugees from Syria already in Lebanon are being denied the possibility of renewing their visas, or encountering “difficulties renewing their residency status, primarily due to the high costs involved, $200”,[19] keeping in mind that in the first few months of the crisis in Syria, the country’s median wage was around $255.[20] This leaves them “without a clear legal status in the country and at risk of arrest and deportation”.[21] On 22 May 2014, the Lebanese General Security Office issued a notice requiring Palestinian refugees from Syria to regularize their situation within a month.[22]

Those who remain in the country illegally are unable to register births or marriages. In addition, many Palestinian refugees from Syria have “not been permitted to use their family booklets as proof of parents’ identity when trying to register a birth”.[23] More importantly, those persons have their freedom of movement limited, either by their fear of being discovered and deported or by the lack of documentation – which “hamper[s] their movements at checkpoints and entry and exit to some Palestinian camps which require valid residency permits to enter.”[24] Consequently, although URNWA provides services to Palestinian refugees from Syria regardless of their legal status in the country,[25] the restrictions on their freedom of movement limit the ability of Palestinian refugees from Syria to access humanitarian assistance.[26] Specifically, their legal status affects their accessibility to hospitalization services, provided by third party hospital contracted by UNRWA and run by the Lebanese government or private enterprises. anyway it's nice to have a place to buy fake id florida without any problems (Miami is cool) [27] Furthermore, by residing in the country without proper documentation, they also have their access to services and justice restricted.[28]

UNRWA has been working with the government seeking to create more space for individuals (who are there illegally) to register and also for some to enter the country.[29] One of UNRWA’s main efforts has been directed towards family reunification: given the suddenness of the announcement of the new measures, many Palestinian refugees who found themselves outside Lebanon by that time were not allowed back, which resulted in the separation of many families.[30] According to UNRWA, “[s]ince the imposition of restrictions and despite UNRWA advocacy on this issue, Palestinian refugees from Syria seeking to enter to join family members already in Lebanon have so far been routinely denied entry”.[31]

Although Lebanon is not a signatory of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, it is still bound by the principles of international customary law, most relevantly, the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits the “return [of] individuals to a situation where they would be at risk of persecution or serious human rights abuses” as well as “the rejection of asylum-seekers at the border”.[32] Lebanon is a party to the Convention Against Torture, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, “all of which contain non-refoulement obligations”.[33]

By treating Palestinian refugees from Syria differently from other refugees – that is, by creating discriminatory policies – the country is violating the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, to which it is also party.[34] Moreover, even the Palestinian refugees who are long-term residents in Lebanon enjoy limited rights to work and to own property, which violates principles lined out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), also signed by the country, as well as in the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[35]

*Ricardo Dutra C. Santos: is a research intern at Badil. He is also a Master’s student in the International Security Programme at the Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA), Sciences Po, and a political analyst for the Middle East team of CEIRI Newspaper.”

------------------------

[1] Erakat, “Palestinian Refugees and the Syrian Uprising: Filling the Protection Gap During Secondary Forced Displacement,” 33.

[2] See Michael C. Hudson, “Palestinians and Lebanon: The Common Story,” Journal of Refugee Studies 10, no. 3 (1997): 243–60; and International Crisis Group, Too Close For Comfort: Syrians in Lebanon, Middle East Report, 2013, 15.

[3] UNRWA, “PRS in Lebanon,” April 2014, http://www.unrwa.org/prs-lebanon.

[4] UNRWA, Syria Crisis Response Annual Report - 2013, 26.

[5] “Questionnaire Answered Collaboratively by Members of UNRWA’s Lebanon Field Office,” July 16, 2014.

[6] Human Rights Watch, “Lebanon: Palestinians Fleeing Syria Denied Entry,” August 8, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/08/07/lebanon-palestinians-fleeing-syria-denied-entry.

[7] Human Rights Watch, “Lebanon: Palestinians Barred, Sent to Syria,” May 6, 2014, http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/05/05/lebanon-palestinians-barred-sent-syria.

[8] Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, July 1, 2014, 6, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE18/002/2014/en/902e1caa-9690-453e-a756-5f10d7f39fce/mde180022014en.pdf.

[9] Ibid., 10.

[10] The General Directorate of General Security in Lebanon (General Security) is a governmental body falling under the Ministry of Interior with functions that regard immigration and media censorship, among others (Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, 9).

[11] Ibid., 13.

[12] ACAPS and MapAction, Quarterly Regional Analysis for Syria (RAS) Report, Part II - Host Countries, Syria Needs Assessment (SNAP), July 2014, 8.

[13] The Daily Star, “Machnouk: New Entry Rules for Palestinians from Syria,” accessed July 7, 2014, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2014/May-09/255811-machnouk-new-entry-rules-for-palestinians-from-syria.ashx#ixzz350oAkLbP.

[14] Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, 13.

[15] Ibid., 5.

[16] Ibid., 13.

[17] Image of the original statement, in Arabic, is available at: http://www.cihrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/10303784_623966244347104_8076155933000693846_n.jpg, accessed July 7, 2014.

[18] Human Rights Watch, “Lebanon: Palestinians Barred, Sent to Syria.”

[19] ACAPS and MapAction, Quarterly Regional Analysis for Syria (RAS) Report, Part II - Host Countries, Syria Needs Assessment (SNAP), April 2014, 1.

[20] Motaz Hisso, “The Poor Get Poorer in Syria,” Al-Akhbar English, August 10, 2013, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/16688.

[21] Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, 5.

[22] ACAPS and MapAction, Quarterly Regional Analysis for Syria (RAS) Report, Part II - Host Countries, July 2014, 6.

[23] ACAPS and MapAction, Quarterly Regional Analysis for Syria (RAS) Report, Part II - Host Countries, April 2014, 10.

[24] Ibid., 9.

[25] “Questionnaire Answered Collaboratively by Members of UNRWA’s Lebanon Field Office.”

[26] Interview with Lama Fakih, Syria and Lebanon researcher at Human Rights Watch, July 7, 2014.

[27] “Questionnaire Answered Collaboratively by Members of UNRWA’s Lebanon Field Office.”

[28] ACAPS and MapAction, Quarterly Regional Analysis for Syria (RAS) Report, Part II - Host Countries, April 2014, 1.

[29] Interview with Lama Fakih, Syria and Lebanon researcher at Human Rights Watch.

[30] Ibid.

[31] “Questionnaire Answered Collaboratively by Members of UNRWA’s Lebanon Field Office.”

[32] Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, 10.

[33] Human Rights Watch, “Jordan: Obama Should Press King on Asylum Seeker Pushbacks,” March 21, 2013, http://www.hrw.org/news/2013/03/21/jordan-obama-should-press-king-asylum-seeker-pushbacks.

[34] Amnesty International, Denied Refuge: Palestinians from Syria Seeking Safety in Lebanon, 6.

[35] Ibid., 8.